One of my very earliest childhood memories is of getting my sticky, sticky hands on one of my brother’s Superman comics. In one panel, it showed how an infant Supes had been loaded into a rocket and fired off from his home planet Krypton in the moments before it was destroyed. The next panel showed the planet coming apart in big fat chunks all flying apart from each other like…well, pretty much like the cover of a Boston album.

I loved that picture of an exploding planet. I loved it so much I spent a fair bit of time on the floor of my parent’s living-room, drawing exploding planets over and over in crayon. Red for the molten core, blue and green for the surface of the chunks speeding away from each other, brown for the jagged pieces of underlying planet-stuff. My obsession lasted probably just about long enough for my parents to start wondering if they had a budding sociopath on their hands…

I was not, of course, obsessed with the end of the world—far from it. I was instead obsessed with science fiction, although I didn’t yet know that was what it was called. As I grew older my obsession broadened until I had no problem skipping from Ballard to Zelazny to Bear and back again. Whether it was Michael Moorcock’s New Wave experimentalism, or Gregory Benford’s harder-than-hard SF, I read it all.

Naturally, some of those stories were indeed about the end of the world, although each imagined apocalypse was often very different from the next. Greg Bear’s The Forge of God depicted the Earth coming apart more or less precisely as it had in that long-ago Superman comic thanks to a pair of black holes orbiting at its core, but that was worlds away from the more oblique, inner-space oriented disasters of JG Ballard’s earlier novels.

The question you have to ask yourself is, why are post-apocalyptic scenarios so popular within the field? In my opinion, these are most often understood as transformative, rather than genuinely apocalyptic events: they’re not so much about the end of the world as they are the birth of a new one. This approach is perhaps most fully realised in “transformative” novels like Ian McDonald’s Chaga and J.G. Ballard’s The Crystal World. Even zombie apocalypse movies, TV shows and comics like The Walking Dead hold out the promise of a world made new, in which those lucky enough to survive (and of course, you always assume you’re one of them) find themselves thrust into a world apparently far more viscerally exciting than the one they previously lived in.

The reality that life under such circumstances is far more likely to be short, brutal and unpleasant is, for the duration of the entertainment, conveniently forgotten.

I remember a meme or cartoon going around at the absolute height of the fashion for zombies in film, books and literature that said something along the lines of admit it, if there was a zombie apocalypse wouldn’t you be just a little bit excited? In a sense, zombie fiction represents a very democratic kind of apocalypse: anyone can be the hero, from the guy who pumps your gas to your elderly next-door neighbour, as long as they’ve got their wits about them and a double-barrelled pump-action shotgun ready to go. In this case, the implied transformation is personal, an opportunity to become a completely different person than the one you were before.

I first touched on apocalyptic events in my own work in my sixth book, Final Days, but that was more about time travel and wormhole physics than it was about the end of the world. I knew, however, that eventually I wanted to create something that focused more directly on “end of the world” scenarios.

I first touched on apocalyptic events in my own work in my sixth book, Final Days, but that was more about time travel and wormhole physics than it was about the end of the world. I knew, however, that eventually I wanted to create something that focused more directly on “end of the world” scenarios.

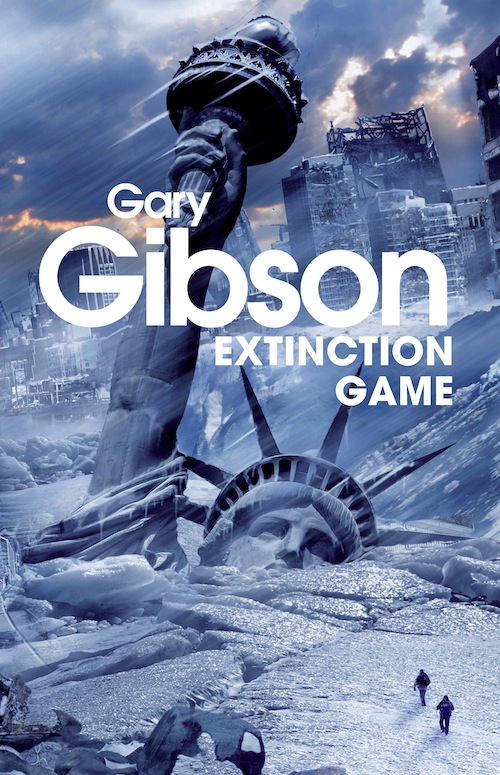

But I wanted to explore more than one possible apocalypse, and in Extinction Game, with its focus on multiple alternate realities, I found the means to stretch a well-worn meme far beyond its traditional parameters. The story of the last man on Earth did not ![]() interest me nearly so much as the story of a man who thinks he’s the last man on Earth, but then find himself in the company of a large number of people who are all the last survivors of apocalypses on different Earths.

interest me nearly so much as the story of a man who thinks he’s the last man on Earth, but then find himself in the company of a large number of people who are all the last survivors of apocalypses on different Earths.

It was inevitable, as I worked on the novel, that in some way or other it would reflect on as well as reference many of those works of apocalyptic fiction with which I had grown up.

With that in mind, following is a list of some of my favourite apocalypses…or more precisely, those stories, novels, movies and comics which in one way or another stuck in my mind long after I read them, and which helped shape my own writing.

Some of the works here are obvious and familiar post-apocalyptic works, while others are…well, less so. But I hope to be able to persuade you that in some way or another, all are deserving of inclusion.

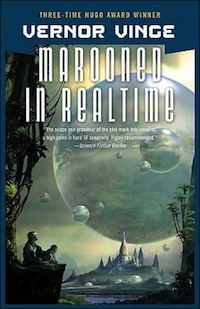

Marooned in Realtime by Vernor Vinge (1986)

Like many other great novels of the SF field, it’s not “just” a post-apocalyptic novel. Instead, it’s several different kinds of story, all seamlessly and ingeniously blended one with another.

Like many other great novels of the SF field, it’s not “just” a post-apocalyptic novel. Instead, it’s several different kinds of story, all seamlessly and ingeniously blended one with another.

When I first picked this up in the mid-Eighties I had no idea it was a sequel to another book called The Peace War (it works very well as a standalone regardless). The protagonist is a detective who’s been “bobbled”—frozen inside a kind of force field within which time ceases to pass until the bobble finally ’bursts’—into the far future. When he finally emerges from his bobble, he finds that long aeons have passed, and that the vast majority of the human race inexplicably vanished some time in the late 22nd century (Jo Walton has a much more in-depth article on Vinge’s novel here that’s very worth checking out).

![]() By the time the story begins, he’s become part of a group of survivors, most of whom voluntarily bobbled themselves a few years forward from their own time only to find the Earth deserted when they finally emerged. Since then, they’ve been bobbling farther and farther into the future, millions of years at a time, gradually collecting other survivors trapped in other bobbles dotted around the globe as and when they burst.

By the time the story begins, he’s become part of a group of survivors, most of whom voluntarily bobbled themselves a few years forward from their own time only to find the Earth deserted when they finally emerged. Since then, they’ve been bobbling farther and farther into the future, millions of years at a time, gradually collecting other survivors trapped in other bobbles dotted around the globe as and when they burst.

It’s an apocalyptic story, in that all of humanity has inexplicably disappeared more or less overnight. It’s also a mystery story, because the survivors badly want to find out how this happened. It’s a detective story, because one of their number is murdered, and the protagonist, a former detective, is put on the case. It’s a hard sf story, both because of the “bobbling” technology and the central thesis regarding the accelerating speed of technological development.

Above and beyond the intricacies of what I regard as one of the most brilliantly plotted books in the field is the question of where the human race went, and it soon becomes clear that Vinge’s preferred answer is that it underwent a technological singularity. On its way to that conclusion, Marooned in Realtime plays with time and destiny on the biggest scale possible. It’s a book I’ve reread many times over the years, and you don’t have to look too hard to see just how much of an influence it’s been on my own writing.

Honourable Mention:

Greg Bear, The Forge of God

The Quiet Earth (dir. Geoff Murphy)

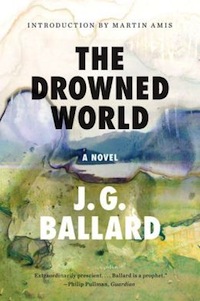

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard (1962)

When I first read this book, I was probably about 12 or 13 and frankly had no idea what the hell was going on. And yet I didn’t care: something about the narrative, and its haunting images of a drowned London slowly slipping back to an earlier, more primordial existence, like a physical manifestation at Carl Jung’s idea of a collective unconsciousness, gripped me like few other works had. It was my first, but by no means my last, Ballard novel.

When I first read this book, I was probably about 12 or 13 and frankly had no idea what the hell was going on. And yet I didn’t care: something about the narrative, and its haunting images of a drowned London slowly slipping back to an earlier, more primordial existence, like a physical manifestation at Carl Jung’s idea of a collective unconsciousness, gripped me like few other works had. It was my first, but by no means my last, Ballard novel.

Catastrophic climate change has raised global temperatures. While what remains of the human race—no more than a few million—has long since fled for the now temperate climate of the far north, an expedition makes its way through a dream-like London submerged beneath deep lagoons.

![]() Rather than attempting to find some way to return the world to its normal state, as might be the case in a more conventional novel, Ballard’s protagonist Kerans instead welcomes the transformed apocalyptic landscape in which he finds himself. He travels there as part of a research team, and along with a few others remains behind when that expedition returns north. Later, pirates arrive, seeking to plunder the crumbling, half-submerged city by draining one of the lagoons. In the process, they revert a part of the city to some semblance of what it had been prior to its abandonment. Kerans, however, doesn’t want the old world back: it’s the new one he wants to be part of, and ultimately he finds a way to flood the lagoon once more.

Rather than attempting to find some way to return the world to its normal state, as might be the case in a more conventional novel, Ballard’s protagonist Kerans instead welcomes the transformed apocalyptic landscape in which he finds himself. He travels there as part of a research team, and along with a few others remains behind when that expedition returns north. Later, pirates arrive, seeking to plunder the crumbling, half-submerged city by draining one of the lagoons. In the process, they revert a part of the city to some semblance of what it had been prior to its abandonment. Kerans, however, doesn’t want the old world back: it’s the new one he wants to be part of, and ultimately he finds a way to flood the lagoon once more.

In this respect, Kerans is the antithesis of the typical “hero” of other disaster novels who might seek to set the world back to rights. As the world around him regresses to something like it had been during the Triassic, Kerans dreams of an ancient ancestral past when great saurian shapes thrashed their way through a world dense with lush jungle.

The novel ends with Kerans fleeing further South, into deeper jungle and greater heat, as if seeking some essential truth buried deep in the primitive lizard-brain of his own deep consciousness.

Honourable Mention:

John Brunner, “The Day The Magic Mushrooms Took Effect” (Omni UK, Autumn, 1984)

Ian McDonald, Chaga (US title: Evolution’s Shore)

Koyaanisqatsi (dir. Godfrey Reggio, 1982)

Although I had caught glimpses of Koyaanisquatsi before on late-night television, it was not until the writer Fergus Bannon invited me and several other then would-be Glasgow writers to watch this film in its entirety sometime in the early 90s that I learned to truly appreciate it. At first glance, it appears to be little more than an admittedly attractive series of stitched-together time-lapse videos of crowded cities, expansive deserts and fast-flowing traffic, set to an entrancing Philip Glass score. However, there is an underlying narrative that makes it much more than this, and the clue lies in the title, which translates from Hopi Indian as “Life out of Balance.”

Although I had caught glimpses of Koyaanisquatsi before on late-night television, it was not until the writer Fergus Bannon invited me and several other then would-be Glasgow writers to watch this film in its entirety sometime in the early 90s that I learned to truly appreciate it. At first glance, it appears to be little more than an admittedly attractive series of stitched-together time-lapse videos of crowded cities, expansive deserts and fast-flowing traffic, set to an entrancing Philip Glass score. However, there is an underlying narrative that makes it much more than this, and the clue lies in the title, which translates from Hopi Indian as “Life out of Balance.”

The implied balance is that between nature and technology, although in this case “nature” refers to both human nature as well as Mother Nature. The movie suggests that the unfettered use of the Earth’s natural resources will lead inevitably to irreversible environmental damage.

The movie has no characters, no dialogue: instead it shows the slow spread of machines, cities, streets and factories, growing ever faster, until humanity spills through its streets and buildings like blood through steel and concrete capillaries. The pace continues to increase, finally culminating in the frankly apocalyptic image of a rocket as it plummets and twists in an out of control descent through the atmosphere: a technological Icarus, wings afire, tumbling towards an Aegean burning bright with artificial light. The message that we must act before it is too late is clear.

But is it post-apocalyptic, you ask? By my definition, very much so. It has a recognisable narrative with a clear theme—a warning, if you like, that seems curiously apt in this age of melting ice caps and global warming.

Collapse by Jared Diamond (2005)

A non-fiction work about the fall of past civilisations, I read Collapse: How Societies Choose To Fail or Succeed not long before I started work on Extinction Game. It’s the reason that much of the action in that book takes place on the Easter Island of a post-apocalyptic parallel universe.

A non-fiction work about the fall of past civilisations, I read Collapse: How Societies Choose To Fail or Succeed not long before I started work on Extinction Game. It’s the reason that much of the action in that book takes place on the Easter Island of a post-apocalyptic parallel universe.

Diamond demonstrates the ways in which a variety of cultures have exhausted the resources available to them to the point where, unable to sustain themselves, they spiral into extinction. The isolated culture of Mauna Loa, as Easter Island was known to its natives, fell first to war, then starvation and finally cannibalism, until only a few straggling survivors remained on a by then denuded island with only its enormous, mysterious statues to hint at a once thriving culture.

![]() The same pattern can be traced repeatedly throughout history (extensive mention is made of the collapse of the Viking community on Greenland), and it’s not hard to extrapolate the author’s observations into our own future.

The same pattern can be traced repeatedly throughout history (extensive mention is made of the collapse of the Viking community on Greenland), and it’s not hard to extrapolate the author’s observations into our own future.

Human nature, as Diamond clearly demonstrates, progresses at a far slower pace than does our technology and our demand for resources.

“A Pail of Air” by Fritz Leiber (short story, 1951)

We’re back on more familiar territory here. I can’t remember how old I was when I first read Fritz Leiber’s short story, but it stuck with me for a long time. The Earth has spun away from its orbit and, having drifted far from the sun’s warmth, the atmosphere has mostly crystallised into a thin, snowy layer clinging to the lifeless soil.

We’re back on more familiar territory here. I can’t remember how old I was when I first read Fritz Leiber’s short story, but it stuck with me for a long time. The Earth has spun away from its orbit and, having drifted far from the sun’s warmth, the atmosphere has mostly crystallised into a thin, snowy layer clinging to the lifeless soil.

Against all odds, a family has somehow managed to remain alive, and one of their daily tasks is to go out of their tiny enclave in homemade spacesuits and sweep up great buckets of frozen atmosphere, which they carry inside. They think they’re the only ones left, until one of them sees a light moving in a building that should be deserted and lifeless.

![]() There’s a scene early on in Extinction Game that very deliberately references this story, and it’s not too hard to spot.

There’s a scene early on in Extinction Game that very deliberately references this story, and it’s not too hard to spot.

Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke (1953)

Although more thoroughly embedded within the tropes of traditional science fiction than, say, Ballard’s The Drowned World, Clarke’s novel also features a species of transformative apocalypse. Earth is visited by vast spaceships that hover over our cities for decades before anyone gets a chance to look directly at the occupants. The purpose of the visit? To help usher the human race towards a new level of existence: children are being born with strange powers, suggesting that the human race is about to undergo a powerful and near-mystic transformation.

Although more thoroughly embedded within the tropes of traditional science fiction than, say, Ballard’s The Drowned World, Clarke’s novel also features a species of transformative apocalypse. Earth is visited by vast spaceships that hover over our cities for decades before anyone gets a chance to look directly at the occupants. The purpose of the visit? To help usher the human race towards a new level of existence: children are being born with strange powers, suggesting that the human race is about to undergo a powerful and near-mystic transformation.

![]() In the end, and as a result of this transformation, the Earth is indeed destroyed. But rather than a cataclysm, it’s once again the birth of a new kind of humanity, a theme that Clarke very much echoed and restated in 2001: A Space Odyssey, his collaboration with Stanley Kubrick.

In the end, and as a result of this transformation, the Earth is indeed destroyed. But rather than a cataclysm, it’s once again the birth of a new kind of humanity, a theme that Clarke very much echoed and restated in 2001: A Space Odyssey, his collaboration with Stanley Kubrick.

Honourable Mention: Greg Bear, Blood Music

The Singularity Is Near by Ray Kurzweil (2005)

Another non-fiction work. I’m sure a lot of people enamoured of the idea of a technological singularity would regard it as anything but apocalyptic, yet contained within that scenario is a kernel of fear that if machines did ever somehow bootstrap themselves to higher and higher levels of intelligence, the first thing they would do is pull a SkyNet and blow us all to Kingdom Come.

Another non-fiction work. I’m sure a lot of people enamoured of the idea of a technological singularity would regard it as anything but apocalyptic, yet contained within that scenario is a kernel of fear that if machines did ever somehow bootstrap themselves to higher and higher levels of intelligence, the first thing they would do is pull a SkyNet and blow us all to Kingdom Come.

But even if you regard such fears as baseless, there is little doubt in my mind that even an apparently benevolent singularity, like the one Vinge more than hints at in Marooned in Realtime, would nonetheless be essentially apocalyptic in nature. A transformative apocalypse, perhaps, but an apocalypse regardless.![]()

The Bed Sitting Room (1969, dir. Richard Lester)

Spike Milligan and others roam the post-nuclear wastes of Britain, ruled over by Mrs. Ethel Shroake of 393A High Street, Leytonstone, the only surviving heir to the British throne. Throughout the movie, characters are randomly mutated by radiation caused by a war that lasted approximately two minutes into wardrobes and, indeed, bed-sitting rooms. A work of post-apocalyptic absurdist joy, like Mad Max remade by Salvador Dali and Groucho Marx. Need I really say more?

Spike Milligan and others roam the post-nuclear wastes of Britain, ruled over by Mrs. Ethel Shroake of 393A High Street, Leytonstone, the only surviving heir to the British throne. Throughout the movie, characters are randomly mutated by radiation caused by a war that lasted approximately two minutes into wardrobes and, indeed, bed-sitting rooms. A work of post-apocalyptic absurdist joy, like Mad Max remade by Salvador Dali and Groucho Marx. Need I really say more?

Honourable Mention:

Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Miracle Mile (dir. Steve de Jarnatt)

When the Wind Blows (graphic novel, Raymond Briggs)

Y: The Last Man (Brian K. Vaughan, 2002–2008)

For some reason, I never actually got around to finishing this comic series—a house move may have intervened—but it was a wild ride nonetheless. Some mysterious force causes the spontaneous death of every man on Earth bar one, leaving the unwilling hero to go on a quest—accompanied by a variety of female companions—to find his girlfriend, last heard from somewhere in the Australian outback.

For some reason, I never actually got around to finishing this comic series—a house move may have intervened—but it was a wild ride nonetheless. Some mysterious force causes the spontaneous death of every man on Earth bar one, leaving the unwilling hero to go on a quest—accompanied by a variety of female companions—to find his girlfriend, last heard from somewhere in the Australian outback.

I grew up reading comics but gave them up when I was about twelve, only to pick up on them again during the early 90s boom. After that petered out, I didn’t really read many more until I came across some of the collected editions at a friend’s house.

![]() Although I still haven’t learned the cause of this particular apocalypse (and I really must get around to finishing it sometime), it almost doesn’t matter because there are few finer examples of the journey being more important than the likely destination. Not only a fine piece of post-apocalyptic fiction, but also a fine piece of comic writing, period.

Although I still haven’t learned the cause of this particular apocalypse (and I really must get around to finishing it sometime), it almost doesn’t matter because there are few finer examples of the journey being more important than the likely destination. Not only a fine piece of post-apocalyptic fiction, but also a fine piece of comic writing, period.

Honourable Mention: The Satan Bug, by Alistair MacLean

Zardoz (dir. John Boorman 1974)

Zardoz is the post-apocalyptic movie with everything you could want. It’s also the movie that people most frequently want to mock, but I think it’s long past the time this movie got some real love.

Zardoz is the post-apocalyptic movie with everything you could want. It’s also the movie that people most frequently want to mock, but I think it’s long past the time this movie got some real love.

I tripped over it on late-night TV who knows how many years ago, and it certainly grabs you. After a brief intro, Sean Connery, resplendent in a handlebar moustache, bright red loincloth and bullet-belt, stows on board a giant flying frickin’ stone head that shouts things like THE GUN IS GOOD, THE PENIS IS EVIL. And that’s just the start of the movie.

Said flying head transports him into a colony of telepaths who long ago returned from a space voyage, only to find civilisation collapsed. Since then they’ve holed up in an enclave protected by a force-field, where they live immortal lives of indolent luxury, frustration and inescapable boredom.

Zardoz has been derided in the past because of its visual appearance, but given the trend in recent years for sf movies that dress their characters in more or less contemporary clothing, listening to more or less contemporary music and talking in entirely contemporary English, regardless of how far in the future they live, you have to wonder whatever happened to the idea that in the future, or on another planet, people might dress, act, think and talk differently.

And in Zardoz, that’s exactly what they do: act, dress and think differently from us, as they should.

Reduced to its most fundamental outline, Sean Connery’s character Zed is a product of the barbarian outlands, as well as of a long-term genetic experiment. His purpose: to bring death to the immortal telepaths, all of whom are thoroughly tired of life. The movie ends with Connery as a literal harbinger of doom, bringing the gift of death to the long-jaded immortals—but only after a series of wildly inventive visual set-pieces.

Honourable Mention: Damnation Alley by Roger Zelazny

Gary Gibson has worked as a graphic designer and magazine editor and began writing at the age of fourteen. His previous novels include the Shoal series (Stealing Light, Nova War and Empire of Light) plus the stand-alone books Angel Stations, Against Gravity, Final Days and The Thousand Emperors. He’s also written a stand-alone novel, Marauder, set in the Shoal series universe. His current project is a series starting with Extinction Game.